Feature: Who is Refereeing NIL?

September 27, 2023

Jalen Rashada signed his national letter of intent to play football at the University of Florida on Dec. 21, 2022. Little did the 19-year-old quarterback know at the time that the commitment would become a part of one of the biggest spats of the college football offseason.

Rashada, the blue-chip Pittsburg (Calif.) High School prospect with a four-star rating from ESPN, was the No. 31 recruit in the 2023 class. He received offers from schools such as the University of Tennessee, the University of Oregon, Oklahoma University, University of Miami, and the University of Florida. Rashada originally committed to Miami, but on Nov. 10 he pulled out of that commitment in order to instead play at the University of Florida.

During the recruiting process with Florida, according to multiple news outlets, Rashada agreed to a name, image, and likeness — or NIL — deal worth a reported $13 million dollars courtesy of the Gator Collective, an organization of UF boosters and alumni. Days before the quarterback was set to enroll in classes at UF for the upcoming spring 2023 semester, Gator Collective informed Rashada that the deal fell through. As a result, Rashada did not enroll in the university, and he asked for a release from his national letter of intent, which Florida ended up granting.

From an outside perspective, it seemed that Rashada left the Gator football program solely because he lost out on that NIL money. On Feb. 1, Rashada signed with Arizona State University (ASU) calling ASU his “childhood dream school” on Twitter.

It was a remarkable feat how Gator Collective was able to offer such a high dollar amount to sign Rashada, but then suddenly pull out of the deal without facing any repercussions themselves. The truth is the world of NIL deals is still largely unregulated by federal and state laws, which can be harmful to college athletics.

“The biggest issue for the NCAA is determining how we adjudicate the NIL rules fairly across all sports, across all three divisions, and across all 50 states,” says Jeff Ligney, commissioner of the Northern Athletics Collegiate Conference. “Without a federal law that governs all NIL issues, different states have created their own NIL laws which has created confusion across the NCAA.”

What started out as a well-meaning attempt to allow players to profit financially off of their name, has turned into a recruiting schematic that can buy players with the sway of a paycheck. However, this is primarily an issue at the Division I and Power Five levels.

“When the idea of NIL came about, it was designed to reward players who were already generating revenue for their chosen institution,” said Ligney. “Now, NIL money is mostly being used as an enticement for student-athletes to enroll at an institution.”

As of right now, the NCAA has not publicly announced detailed rules or regulations regarding NIL, and companies are allowed to offer as much money as they wish to prospective student-athletes.

“To my knowledge, there are no laws that govern this kind of activity,” said Ligney. “This could be very damaging to students if these consortiums are not held responsible for these offers.”

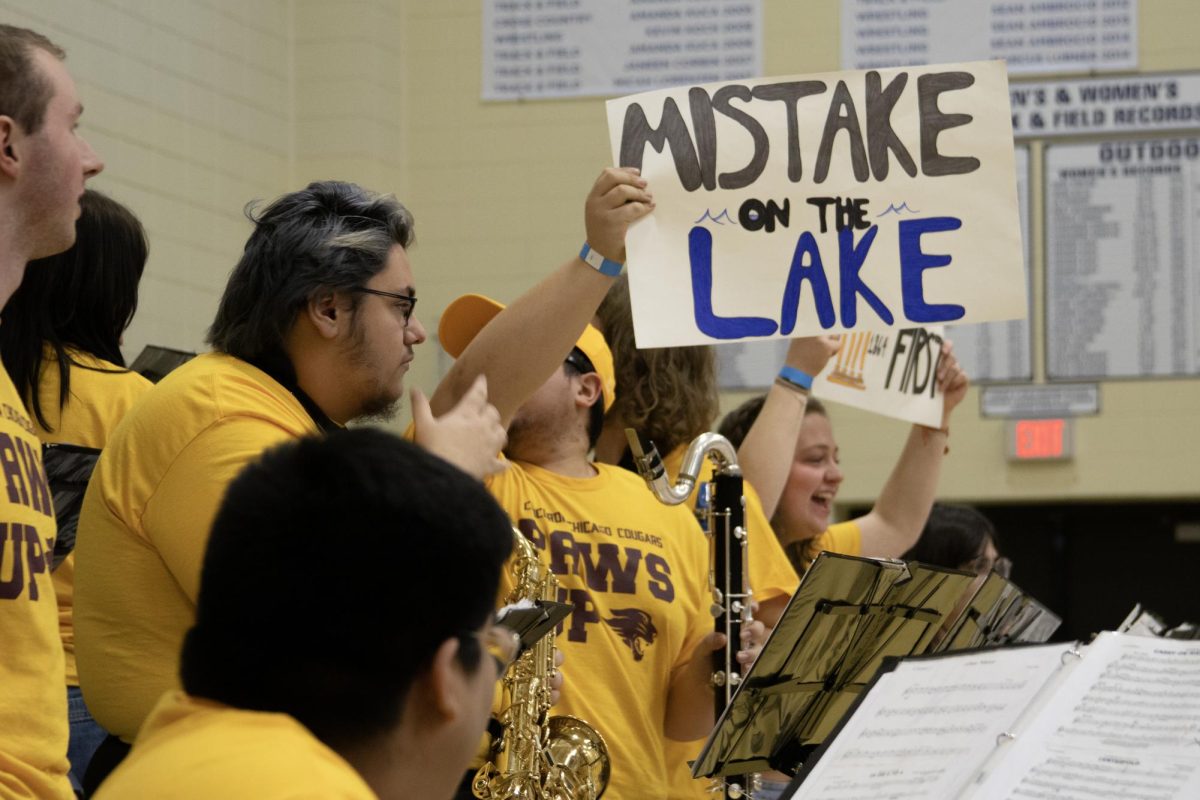

NIL is a hot-button issue for many collegiate athletes such as Dayton Sneed, a freshman wide receiver at the University of Tennessee. “NIL is out of control,” said Sneed. All Tennessee Volunteer football players are guaranteed $6,000 in NIL through the university. “You see other schools buying their players, but just because you have money doesn’t make you successful,” Sneed added.

In 2022, for example, the Texas A&M Aggies finished with college football’s No. 1 recruiting class in the nation tallying commitments from eight five-star recruits and 20 four-star recruits. Despite these top-ranked signings, however, the Aggies posted a 5-7 record the following regular season and finished with one of the statistically worst offenses in all of college football.

“I think it’s a little ridiculous,” said Sneed. “Some players do it for the money, not for the love of the game, and I think it’s a little toxic.”

Ligney claims the NCAA recognizes that this is an issue and says that they are attempting to take precautionary measures.

“The NCAA is working with federal legislators in both the House of Representatives and the Senate to create a federal NIL law,” said Ligney. “But the federal government and the state governments cannot decide under which jurisdiction NIL resides.”

Even though NIL may be an issue for some people, it has proven to be very beneficial for other players. Dont’e Thornton, who is a current teammate of Sneed and a junior wide receiver at the University of Tennessee, loves the idea of college-athletes being able to bring in money for themselves.

“I feel like NIL is a good thing because it is giving colleges an opportunity to make money,” said Thornton. “Then, that money can be used for a lot of different things.”

Thornton, who is originally from Baltimore, Md., was a four-star signee to the University of Oregon in the 2021 recruiting class. During his two seasons with the Ducks, he totaled 541 yards and three touchdowns on 26 receptions. Thornton entered the transfer portal on Nov. 28, 2022, before committing to play for University of Tennessee head coach, Josh Heupel, and the Volunteers on Jan. 9.

Thornton understands the impact NIL has on collegiate athletes, and he wishes that this policy could have been implemented earlier.

“I personally don’t have a problem with it,” said Thornton. “I actually wish this was something that started earlier so more people could’ve taken advantage of it.”

There is no debating NIL can have some positive effects on many student-athletes. However, since NIL’s introduction on July 1, 2021, the NCAA has been very lenient on letting schools dictate their own rules regarding the policy. A few years ago, it was considered an NCAA violation to recruit student-athletes that had already signed their letter on intent to play for a specific institution.

“Many consortiums representing Division I and Power Five institutions are now ignoring those rules,” said Ligney. “The NCAA no longer has the teeth to enforce those rules.”

As a result, we are seeing student-athletes transfer to schools that will give them the best NIL deals. So far in the college football offseason, more than 1,300 athletes entered the transfer portal – which is the highest number of transfers since the portal was introduced in 2018.

This article was part of the coursework for JOU-3200 Feature Writing in Spring 2023.